From an interview with Superbugs

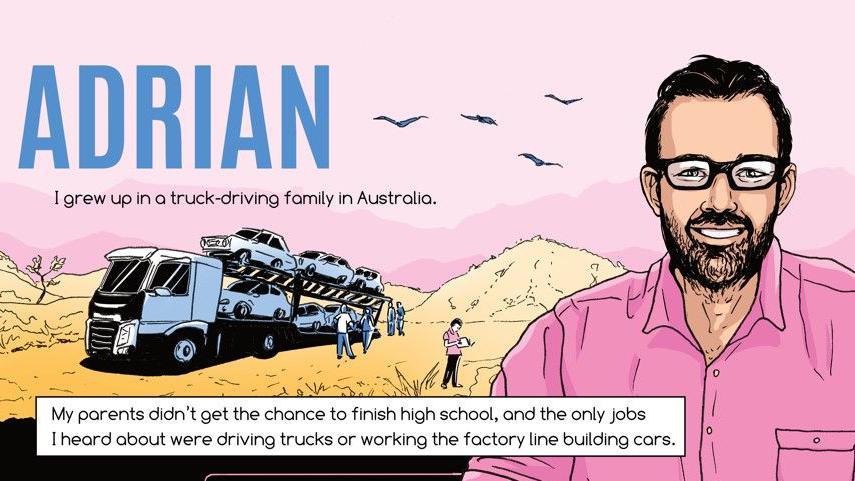

I didn’t really know what a scientist was growing up in Australia. My Dad was a truck driver, and everyone around me either drove trucks or worked in factories. If it wasn’t for watching nature documentaries on the TV, I probably would have dropped out of high school and become a truck driver too. Listening to David Attenborough explain how life was interconnected changed my pathway in life. I had a taste of wondering “why” and hearing it explained, and I wanted to know how the how world worked.

I got good grades in school and went to university. Although, to be honest, you didn’t need especially good grades to get into a science degree – it is rather inclusive entry, unlike medicine or engineering which are tougher to get into. I’m also not especially convinced that the grades you get during your degree in science reflect much about your capacity to be a scientist. The undergraduate degree has to give you the baseline of facts and tools, but once you graduate and become a scientist you are operating at the very boundary of human knowledge. It doesn’t matter if you are quick or slow, have a photographic memory or need to look up basic formulas each time. Science is different from any other walk in life. You can fail and fail and fail, but by succeeding just once you add something new to the sum total of humanity’s knowledge. When I think about what it takes to succeed as a scientist I think it really comes down to three things: creativity, resilience and integrity.

Why creativity, resilience and integrity? Creativity because we don’t know what the right experiments are. Once you are at the boundaries of knowledge, all you can do is take an educated guess, design the best experiment you can, and see if it sheds new light. Most of the time it doesn’t! So a creative scientist is someone who is good at coming up with multiple different ways to attack a problem. Of course, this means a lot of failure, which is where resilience comes in. Failing multiple times is a serious downer. Classical high achievers often struggle when they transition from acing every exam to failing in the lab. If you’ve got grit, if you know how to pick yourself up and try again, then you’ll eventually solve the problem. That is what science is, being wrong over and over again, until in the end you are right. Finally, integrity is key. You’ve just got to be honest in science. To make progress we need to build a tower out of data. People who are willing to fudge their results, fool themselves into thinking they are right when they are not, they start building their tower on poor foundations. The scientists who are willing to admit they are wrong, change their mind with new data, and take the slow route are the ones who end up building the highest.

I guess this doesn’t make science sound super attractive as a career! It is genuinely hard, and few people actually enjoy being wrong over and over again! But the thing is, when you are right, it is amazing. When we find something out it is actually something entire new that we have created – we have moved the sphere of human knowledge further out. There are also a lot of perks to a career in science – I get to travel a lot, don’t need to wear a suit, and the work is easier and for more money than driving a truck or working in a factory!

For myself, after a research career in Australia and America, I started to become more interested in creating a space for scientists to excel in, rather than doing science myself. I moved to Belgium and set up a lab in a hospital there. I tried to bring in a team of amazing people with different skills and backgrounds – biologists, mathematicians, clinicians, engineers, chemists and more, precisely because we never really know the best way to tackle the new problem. My job is to pick the questions we work on, and help the team to find ways to put together their skills to answer those questions. By having a team of diverse people who think in different ways we became much more successful at finding a winning formula. We have uncovered the causes of human diseases, solved riddles for why some patients are sick, started clinical trials that brought new treatments to neglected patients, even developed new drugs. Each success we have opens up a new and more interesting problem, and we are genuinely improving the world.

After a decade in Belgium I moved over my lab to Cambridge. We are still working on interesting problems in pathology, and I still have an amazing team of diverse scientists. Perhaps the best part, though, is that so many people have left my lab and have started up their own teams, in universities, hospitals and biotech companies, all across the world. That decision I made to go into science after high school has led to hundreds of scientists being trained, and humanity will build on the knowledge they create long after I am gone.

Thursday, January 29, 2026 at 11:42AM

Thursday, January 29, 2026 at 11:42AM

Liston lab,

Liston lab,  science careers

science careers