Graphic novel shows unconventional routes into science

Sunday, September 29, 2024 at 1:39PM

Sunday, September 29, 2024 at 1:39PM Stories of people's unconventional routes to becoming scientists are told in a new graphic novel intended to encourage others into the field.

The book - Becoming a Scientist - is aimed at young adult readers and was written by the University of Cambridge's Prof Adrian Liston, and illustrated by Yulia Lapko - a business administrator for the pathology department.

Both their routes could be deemed unconventional as Prof Liston was expected to join his truck-driving family's business in Australia, while Ms Lapko fled her native Ukraine in 2022 following invasion.

Prof Liston said as a youngster he did not even know what a scientist was, and hoped the stories showed the "many different pathways".

The novel told the stories of 12 members of the Liston-Dooley lab, who researched the immune system and tissues during pathology.

This was not Prof Liston's first book and he has written books for young children including All about Coronavirus, Battle Robots of the Blood and Maya’s Marvellous Medicine.

His graphic novel, however, was aimed at older readers between 12 and 18 years of age.

Stories about how the team members came to work in science are told in the graphic novel

"It was really luck more than anything else that allowed me to fall into the career I have today," Prof Liston said.

"When I looked around the amazing people in my lab, I realised that everyone had a story about overcoming barriers to enter science."

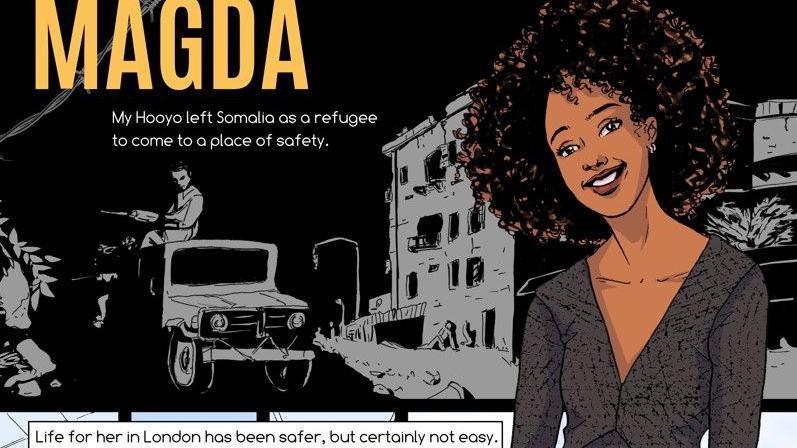

Magda Ali, Ntombizodwa Makuyana and Amy Dashwood became models for the cover of the book

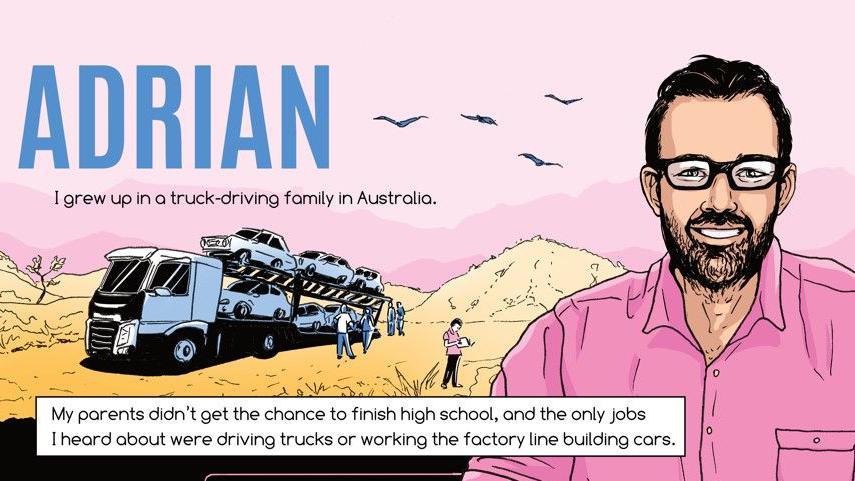

Prof Liston freely admits he was not brought up to be a scientist.

In the book, he said: "I grew up in a truck-driving family in Australia.

"My parents didn't get the chance to finish high school and the only jobs I heard about were driving trucks or working the factory line building cars."

He added: "I never met a scientist. Actually, if I hadn't been inspired by the weekly nature documentary on TV I'd never have known being a scientist was possible."

Adrian Liston was inspired to follow a scientific education after watching nature programmes on television

Studying at university was "an epiphany for me", the professor said.

"Sure, there was class snobbery, but I was also able to find my group who were weird like me."

He told the BBC: "I want to see more kids with grit and creativity really look seriously at science as a potential career, and I realised that my team here at Cambridge really demonstrated just how diverse scientists are in practice.

"Every one had their own story of adversity conquered, their own role-models and their own motivations, so I thought we could simply tell their stories.

"While each one is unique, together they do show that science can be for anybody, and science becomes richer for having a diversity of talents."

Magda Ali pursued her education because she dreamt of becoming a scientist

Other stories included those of Magda Ali, who is completing her PhD at Cambridge University. Her parents came to the UK as refugees from Somalia and although she attended a school where few students even took A-levels, she continued her studies and her dream of becoming a scientist.

Visiting student researcher Alvaro Hernandez said he failed his school entrance tests in Peru at the age of five and almost did not get an education at all, having been preoccupied instead with football.

"I think my early teachers would be surprised to see me in Cambridge," he said in the book.

Their diverse stories have been illustrated by Yulia Lapko, who came to the UK under the Homes for Ukraine scheme.

Yulia Lapko came to the UK after her native Ukraine was invaded by Russia

She had been working as an artist before the war, but on arriving in Cambridge, and added: "I took a break from that because, settling in the new country, it made sense to get a full-time job for a sense of security and stability. Now that I feel settled enough I can expand the possibilities of what I can do with my skills.

"I really enjoy being here, I love the department and its people.

"Drawing people is my main speciality in art, and all the people featured in the book I actually see every day, which made it easier to capture them in a way that feels alive and effortless.

"But it’s one thing to see what people look like and the other is to really see them, to know the story behind each individual, so having all of them share their backgrounds, hopes and wishes really helped to get the whole picture of each character."

Prof Liston added: "It is guts and heart rather than brains that lead to scientific breakthroughs, and every discovery worth making happens from a team."

Read the book for free online or order a print copy.