Vaccines are very unusual medicines. Most medications are developed for the purpose of treating sick people. Vaccines, on the other hand, are developed for the purpose of treating healthy people, ideally for an infection that most people won't get exposed to. This means that vaccine development is in one way much harder than any other drug. This is because every medication needs to do more good than harm to the person receiving it. A drug designed to treat a disease has an easy cost-benefit ratio to achieve: if that disease is serious and the drug is effective in at least some people, then even relatively frequent adverse effects may be tolerated. In the case of vaccines, however, because you are treating healthy people the cost-benefit ratio means you can almost never have any substantial adverse effects and the vaccine has to work in almost every person. Add on to this the fact that vaccines are designed to give ideally life-long protection. A drug for a disease might be acceptable if it worked if taken once a day. A vaccine should give at least 10 years of protection, although there are a few exceptions. Plus vaccines are most effective when everyone gets them, meaning you need to be able to mass produce them for almost nothing and they should be stable even without cold storage, etc. In short, vaccines are exceptionally difficult to make because they have to be nearly perfect before they get approved.

On the other hand, vaccines are easier to make than most other drugs. For most drugs, we first need to understand the molecular basis of disease in incredible detail, down to the atomic precision of the key proteins. Only then can we start to design small molecules that disrupt pathology, with a long and painful process of screening and improving that leaves most drug candidates dead before they hit a trial. Even once we get into patients, we are still highly likely to find that the drugs do more harm than good, or are only effective in a handful of patients. Vaccines, on the other hand, are not really drugs at all. You can best think of a vaccine as a trigger to instruct the body on how to make its own natural drugs, antibodies. The more we know about a virus the better we can design the vaccine trigger, but a lot of the best vaccines just come from randomly blasted bits of dead virus. There are exceptions, where the viruses biology works against us. HIV and herpes viruses are really difficult to make vaccines against, because they hide out inside our body. Fortunately, COVID-19 looks like a fairly standard virus in this respect, and is unlikely to be unusually problematic. There are already promising small-scale trials indicating that antibodies against COVID-19 would work. These were done by taking antibodies from a recovered patient and injecting it into the sick patient, but the principle is the same. There is still some concern that COVID-19 may be more complicated, based on some results indicating that recovered people can get reinfected, but at the moment this is most likely due to false negative screening rather than a true re-infection. It does need to be considered though - we just don't know enough about the biology to be sure.

With vaccines being both harder and easier to make than other drugs, how long will it be before we get a vaccine? Here I don't have any inside commercial knowledge, but it seems very likely that we will have a vaccine developed, tested and approved in 2020. The key here is that the cost-benefit ratio is completely different for a COVID-19 vaccine than it is for a normal vaccine. As I said, normal vaccines have to be almost perfect before they are approved, with any serious side-effects resulting in the vaccine being shelved. During a global pandemic, however, the risk of adverse effects needs to be balanced against the advantage of moving fast. Let's say we got a vaccine that only worked in 50% of people and caused minor adverse effects (sore arm for a week) in 10% of people. Right now, who wouldn't line up to get vaccinated?

So expect a poor vaccine in 2020, assuming that immunologists are given sufficient funding to develop it. It will skip a lot of the normal safety and efficacy steps, and it will likely not protect everyone and possibly cause side-effects. That said, it would still be a useful tool for controlling a pandemic. Then towards the end of 2021 I would expect to see the roll-out of better vaccines, with higher levels of efficacy and fewer adverse effects. At some point in the future, every child will likely be given a vaccine for COVID-19 as part of their routine vaccination schedule, but that is much more likely to be a third- or forth-generation vaccine, with the optimal properties that we expect.

Wednesday, April 1, 2020 at 11:02AM

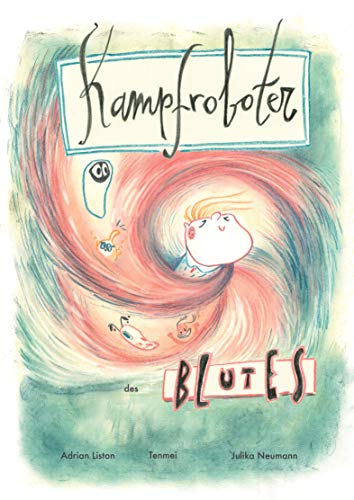

Wednesday, April 1, 2020 at 11:02AM  Tim ist ein ganz normaler 7-jähriger Junge, der wegen eines genetischen Defekts in seinem Immunsystem eine Immundefizienz hat. Es ist eine Geschichte über Tom's Leben und wie das Immunsystem funktioniert. Jeden Monat zur Behandlung ins Krankenhaus zu gehen ist ein ganz normaler Teil seines Lebens. Er versteht die ganze Aufregung nicht wirklich, aber er weiß, dass seine Eltern sehr besorgt sind, wenn er krank wird. Für Tim ist es viel wichtiger, dass seine Freunde alle geimpft sind, damit sie jederzeit mit ihm spielen und ihn dabei nicht anstecken können.

Tim ist ein ganz normaler 7-jähriger Junge, der wegen eines genetischen Defekts in seinem Immunsystem eine Immundefizienz hat. Es ist eine Geschichte über Tom's Leben und wie das Immunsystem funktioniert. Jeden Monat zur Behandlung ins Krankenhaus zu gehen ist ein ganz normaler Teil seines Lebens. Er versteht die ganze Aufregung nicht wirklich, aber er weiß, dass seine Eltern sehr besorgt sind, wenn er krank wird. Für Tim ist es viel wichtiger, dass seine Freunde alle geimpft sind, damit sie jederzeit mit ihm spielen und ihn dabei nicht anstecken können. science communication

science communication